Table of Contents Link to heading

- Introduction

- Idea behind variational inference

- Variational families

- ELBO optimization

- Estimating the average number of active players in an mmorpg

- Document clustering with LDA

Probabilistic models like logistic regression, Bayesian classification, neural networks, and models for natural language processing, are increasingly more present in the world of data science and machine learning. If you want to use these models for reliable infernce (such as prediction), you should always do your best to carry out some type of uncertainty quantification (UQ) which will give you a good idea about the limits of models you used. Bayesian statistics is typically the go-to method for UQ, because it allows to naturally express uncertainties in the language of probability.

In many settings, a central task task in UQ of probabilistic models is the evaluation of posterior distribution $p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y})$ of $m$ model parameters conditioned on the observed data $\bold{y} = (y_1, \dots, y_n)$ provided by the Bayes’ theorem

$$ p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y}) = \frac{p(\bold{y} \mid \bold{\theta})p(\bold{\theta})}{p(\bold{y})} \propto p(\bold{y} \mid \bold{\theta})p(\bold{\theta}).$$

Here, $p(\bold{y} \mid \bold{\theta})$ is the sampling density given by the underlying probabilistic model for data, $p(\bold{\theta})$ is the prior density that represents our prior beliefs about $\bold{\theta}$ before seeing the data, and $p(\bold{y})$ is the marginal data distribution. The posterior distribution, however, has closed form only in a limited number of scenarios (e.g., conjugate priors) and therefore typically requires approximation. By far the most popular approximation methods are Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms including Gibbs sampler, Metropolis, Metropolis-Hastings, and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (See the Bayesian bible for overview of these methods). While useful for simple models with moderately-sized dataset, these MCMC algorithms do not scale well with large datasets and can have a hard time approximating multimodal posteriors. These challenges limit the applications of probabilistic models with massive datasets needed to train neural networks, pattern recognition algorithms, or models for natural language processing. In the rest of this post, I want to give you a gentle introduction to Variational inference, which is an alternative to the sampling-based approximation via MCMC that approximates a target density through optimization and tends to scale well to massive dataset.

Idea behind variational inference Link to heading

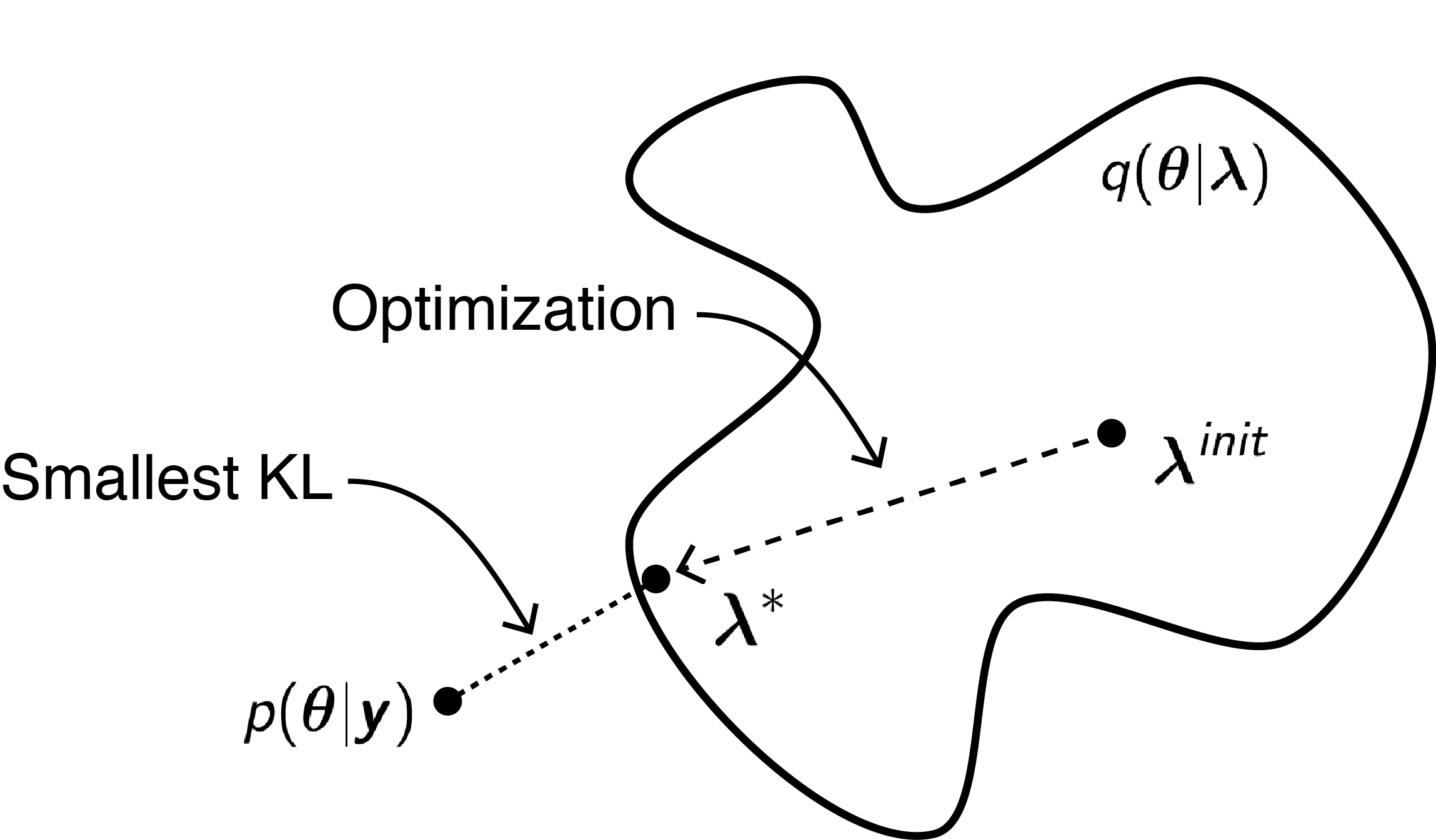

The main idea behind variational inference is to approximate the target probability density $p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y})$ by a member of some relatively simple family of densities $q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})$, indexed by the variational parameter $\bold{\lambda} \in \mathbb{R}^{m}$ ($m \geq 1$), over the space of model parameters $\bold{\theta}$. Note that $\bold{\lambda}=(\lambda_1, \dots, \lambda_m)$ has $m$ components of (potentially) varying dimensions. Variational approximation is done by finding the member of variational family that minimizes the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence of $q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})$ from $p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y})$:

$$q^* = \argmin_{q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})} KL(q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})||p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y})), $$

with KL divergence being the expectation of the log ratio between the $q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})$ and $p(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{y})$ with respect to $q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})$. Intuitively (though it is not exactly true), the KL divergence measures how different is the variational approximation from the posterior distribution. In a nutshell, rather than sampling, variational inference approximates densities using optimization, i.e., by finding the values of variational parameters which lead to a variational distribution that is close to the target posterior distribution. See the figure below for a graphical illustration of this idea.

Finding the optimal $q^*$ is done in practice by maximizing an equivalent objective function, $\mathcal{L}(\bold{\lambda})$, the evidence lower bound (ELBO), because the KL divergence is intractable as it requires the evaluation of the marginal distribution $p(\bold{y})$:

$$\mathcal{L}(\bold{\lambda}) = \mathbb{E}_q[\log p(\bold{y}, \bold{\theta}) - \log q(\bold{\theta}|\bold{\lambda)} ] $$

Variational families Link to heading

Let’s now move on to the implementation details of variational inference starting with the selection of the variational family $q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda})$. This choice is crucial as it affects the complexity of optimization as well as the quality of variational approximation.

Mean-field Variational Family Link to heading

One of the most popular families is the mean-field variational family which assumes that all the unknown parameters are mutually independent, each approximated by its own univariate variational density: $$ q(\bold{\theta} \mid \bold{\lambda}) = \prod_{i=1}^{m} q(\theta_i \mid \bold{\lambda}_i). $$

For example, a typical choice for real-valued parameters is the normal variational family $q(\theta \mid \mu, \sigma^2)$ and the log-normal or Gamma for non-negative parameters. The main advantage of the mean-field family is in its simplicity as it requires only a minimum number of parameters to be estimated (no correlation parameters) and often leads to uncomplicated optimization. However, the mutually independent parameter assumption comes at a price because the mean-field family cannot capture relationships between model parameters. To see more comprehensive review of more complex variational families, take a look here. If would definitely recommend googling normalizing flows if you want to get serious about using VI.

ELBO optimization Link to heading

Besides the choice of variational family, another key implementation detail to address is the way in which one finds the member of the variational family that maximizes the ELBO. Since this is a fairly general optimization problem, one can in principle use any optimization procedure. In the VI literature, the coordinate ascent and the gradient ascent procedures are the most prominent and widely used.

The coordinate ascent approach is based on the simple idea that one can maximize ELBO, which is a multivariate function, by cyclically maximizing it along one direction at a time. Starting with initial values (denoted by superscript $0$) of the $m$ variational parameters $\bold{\lambda}^0$

$$ \bold{\lambda}^0 = (\bold{\lambda}^0_1, \dots,\bold{\lambda}^0_m), $$

one obtains the $(k+1)^{\text{th}}$ updated value of variational parameters by iteratively solving

$$ \lambda_i^{k + 1} = \argmax_{x} \mathcal{L}(\lambda_1^{k + 1}, \dots, \lambda_{i-1}^{k + 1}, x, \lambda_{i + 1}^k, \dots, \lambda_m^k), $$ which can be accomplished without using gradients.

Variational inference via gradient ascent uses the standard iterative optimization algorithm based on the idea that the ELBO grows fastest in the direction of its gradient. In particular, the update of variational parameters $\bold{\lambda}$ at the $(k+1)^{\text{th}}$ iteration is given by $$ \bold{\lambda}^{k+1} \leftarrow \bold{\lambda}^{k} + \eta \times \nabla_{\bold{\lambda}} \mathcal{L}(\bold{\lambda}^{k}), $$ where $\nabla_{\bold{\lambda}} \mathcal{L}(\bold{\lambda})$ is the ELBO gradient, and $\eta$ is the step size which is also called the learning rate. The step size controls the rate at which one updates the variational parameters.

Although both coordinate and gradient methods are in principle nice and simple, they are inefficient for large datasets. To truly unlock the speed of VI it has become common practice to use the stochastic gradient ascent (SGA) algorithm. SGA in principle works the same way as the standard gradient ascent except one can use simple and fast-to-compute unbiased estimate of the gradient instead of the gradient based on the full training dataset.

Estimating the average number of active players in an mmorpg Link to heading

To see how ELBO optimization leads to a good approximation of target posterior distribution, let us consider Poisson sampling with a Gamma prior, which is a popular one-parameter model for count data. Suppose that you work for a game developer and your task is to estimate the average number of active users of a popular massively multiplier online role-playing game (mmorpg) playing between the peak evening hours 7 pm and 10 pm. This information can help game developers in allocating server resources and optimizing user experience. To estimate the average number of active users, we will consider the following counts (in thousands) of active players collected during the peak evening hours over a two-week period in the past month.

| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | 50 | 47 | 46 | 52 | 49 | 55 | 53 |

| Week 2 | 48 | 45 | 51 | 50 | 53 | 46 | 47 |

Gamma-Poisson model Link to heading

Suppose $\bold{y} = (y_1, \dots, y_n)$ represent the observed counts in $n$ time intervals where the counts are independent, and each $y_i$ follows a Poisson distribution with the same rate parameter $\theta > 0$. The joint probability mass function of $\bold{y} = (y_1, \dots, y_n)$ is

$$p(\bold{y} \mid \theta) \propto \prod^{n}_{i=1} \theta^{y_i} e ^{-\theta}. $$

The posterior distribution for the rate parameter $\theta$ is our inference target as $\theta$ represents the expected number of counts that occurs during the given time intervals. Note that the Poisson sampling relies on several assumptions about the sampling process: One assumes that the time interval is fixed, the counts occurring during different time intervals are independent, and the rate $\theta$ at which the counts occur is constant over time. The Gamma-Poisson conjugacy states that if $\theta$ follows a Gamma prior distribution with shape and rate parameters $\alpha$ and $\beta$, it can be shown that the posterior distribution $p(\theta \mid \bold{y})$ will also have a Gamma density. Namely, if

$$\theta\sim \textrm{Gamma}(\alpha,\beta),$$ then

$$\theta \mid \bold{y} \sim \textrm{Gamma}(\alpha+ \sum_{i=1}^n y_i, \beta + n). $$

In other words, given $\alpha$, $\beta$, and $\bold{y}$, one can derive the analytical solution to the posterior of $p(\theta \mid \bold{y})$ and can subsequently sample from $\textrm{Gamma}(\alpha+ \sum_{i=1}^n y_i, \beta + n)$ to get posterior samples of $\theta$. So it turns out that actually no approximation is needed in this case, but it will serve as a good example to illustrate how VI works.

Recall that VI approximates the (unknown) posterior distribution of a parameter by a simple family of distributions. In this Gamma-Poisson case, we will approximate the posterior distribution $p(\theta \mid \bold{y})$ by a log-normal distribution with mean $\mu$ and standard deviation $\sigma$:

$$ q(\theta \mid \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\theta \sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(\ln{\theta} - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}.$$

It is a popular variational family for non-negative parameters because it can be expressed as a (continuously) transformed normal distribution, and therefore it is amenable to automatic differentiation (this will make a lot of sense if you googled normalizing flows).

Enough of the general discussion about the Gamma-Poisson model and let us dig into estimating the average count of an mmorpg’s active players. Suppose that you asked your expert colleague for an advice on the matter, and they tell you that a similar mmorpg has typically about 50,000 users during peak hours. However, they are not too sure about that, so the interval between 45,000 and 55,000 users should have a reasonably high probability. This reasoning leads to a $\textrm{Gamma}(100,2)$ as a reasonable prior for the average number of active users. If you payed attention in the paragraph above, you know that the true posterior distribution is $\textrm{Gamma}(792, 100)$. Play with the sliders in the Shiny app below to manually find the member of a log-normal variational family that well approximates the posterior distribution of $\theta$. Check the Fit a variational approximation box in the app to find the variational approximation using the gradient ascent algorithm.

Document clustering with LDA Link to heading

Enough of playing with simple examples, let us use VIto implement the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model in R and apply to a dataset of documents. To do so, we will analyze a collection of 2246 Associated Press newspaper articles to be clustered using the LDA model. The dataset is part of the topicmodels package. You can load the dataset AssociatedPress with the following R command.

data("AssociatedPress", package = "topicmodels")The LDA is a mixed-membership clustering model, commonly used for document clustering. LDA models each document to have a mixture of topics, where each word in the document is drawn from a topic based on the mixing proportions. Specifically, the LDA model assumes $K$ topics for $M$ documents made up of words drawn from $V$ distinct words. For document $m$, a topic distribution $\bold{\theta_m}$ is drawn over $K$ topics from a Dirichlet distribution, $$\bold{\theta}_m \sim \textrm{Dirichlet}(\bold{\alpha}),$$

where $\sum_{k=1}^{K}\theta_{m, k} = 1$ ($0 \leq \theta_{m, k} \leq 1$) and $\bold{\alpha}$ is the prior vector of length $K$ with positive values.

Each of the $N_m$ words ${w_{m, 1},\dots, w_{m, N_m}}$ in document $m$ is then generated independently conditional on $\bold{\theta_m}$. To do so, first, the topic $z_{m, n}$ for word $w_{m, n}$ in document $m$ is drawn from

$$z_{m, n} \sim \textrm{categorical}(\bold{\theta}_m),$$

where $\bold{\theta_m}$ is the document-specific topic-distribution. Next, the word $w_{m, n}$ in document $m$ is drawn from

$$w_{m, n} \sim \textrm{categorical}(\bold{\phi}_{z[m, n]}),$$

which is the word distribution for topic $z_{m, n}$. Lastly, a Dirichlet prior is given to distributions $\bold{\phi}_k$ over words for topic $k$ as

$$\bold{\phi}_k \sim \textrm{Dirichlet}(\bold{\beta}),$$

where $\bold{\beta}$ is the prior a vector of length $V$ (i.e., the total number of words) with positive values.

There are many packages out there that have native support for VI. If you want to sue R, I recommend using the CmdStanR, which is a lightweight interface to Stan for R users. I am not recommending to use the plain RStan if you are interested in extracting the ELBO trajectory which is not at all straightforward with RStan without doing some hacking. If you are familiar with RStan working with CmdStanR is not whole that different. For instance, models are defined in the same way as with SRtan:

data {

int<lower=2> K; // number of topics

int<lower=2> V; // number of words

int<lower=1> M; // number of docs

int<lower=1> N; // total word instances

int<lower=1, upper=V> w[N]; // word n

int<lower=1, upper=M> doc[N]; // doc ID for word n

vector<lower=0>[K] alpha; // topic prior vector of length K

vector<lower=0>[V] beta; // word prior vector of length V

}

parameters {

simplex[K] theta[M]; // topic distribution for doc m

simplex[V] phi[K]; // word distribution for topic k

}

model {

for (m in 1:M)

theta[m] ~ dirichlet(alpha);

for (k in 1:K)

phi[k] ~ dirichlet(beta);

for (n in 1:N) {

real gamma[K];

for (k in 1:K)

gamma[k] = log(theta[doc[n], k]) + log(phi[k, w[n]]);

target += log_sum_exp(gamma); // likelihood;

}

}Let’s fit a two-topic LDA model (i.e., $K = 2$). Before that, I recommend removing the words from AssociatedPress datasets that are rare using the function removeSparseTerms() from the tm package. These words have a minimal effect on the LDA parameter estimation and unnecessarily increase the computational cost.

dtm <- removeSparseTerms(AssociatedPress, 0.95)You are now ready to fit the LDA model using VI capabilities of the CmdStanR. The following code achieves the goal:

LDA_model_cmd <- cmdstan_model(stan_file = "LDA.stan")

N_TOPICS <- 2

data <- list(K = N_TOPICS,

V = dim(dtm)[2],

M = dim(dtm)[1],

N = sum(dtm$v),

w = rep(dtm$j,dtm$v),

doc = rep(dtm$i,dtm$v),

#according to Griffiths and Steyvers(2004)

alpha = rep(50/N_TOPICS,N_TOPICS),

beta = rep(1,dim(dtm)[2])

)

vi_fit <- LDA_model_cmd$variational(data = data,

seed = 1,

output_samples = 1000,

eval_elbo = 1,

grad_samples = 10,

elbo_samples = 10,

algorithm = "meanfield",

output_dir = NULL,

iter = 1000,

adapt_iter = 20,

save_latent_dynamics=TRUE,

tol_rel_obj = 10^-4)The LDA.stan file contains the Stan script for the LDA model. To access the ELBO values, use the following:

vi_diag <- utils::read.csv(vi_fit$latent_dynamics_files()[1],

comment.char = "#")

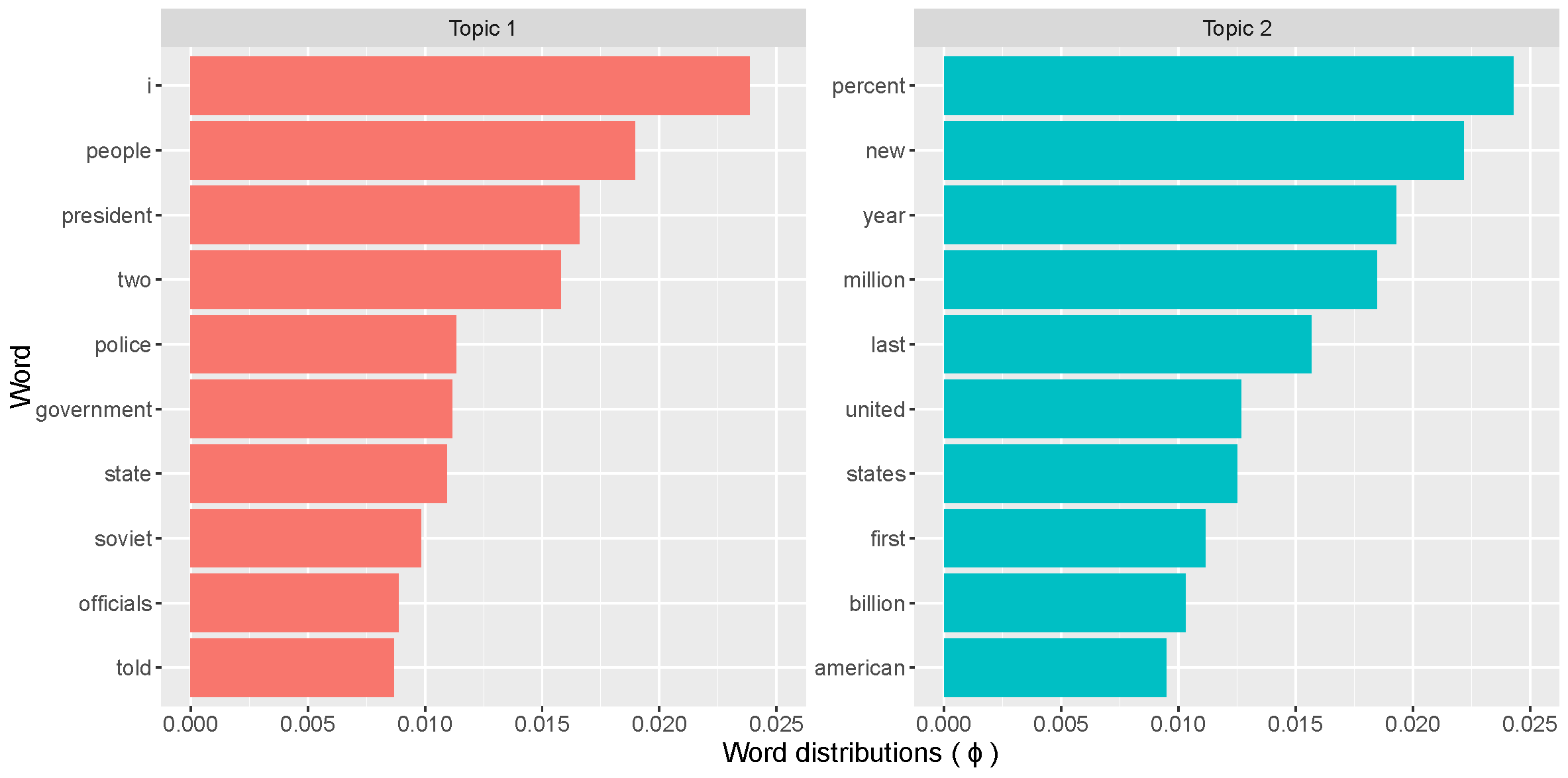

ELBO <- data.frame(Iteration = vi_diag[,1], ELBO = vi_diag[,3])To display the topics that were extracted from the collection of articles using the LDA you can show the 10 most common words for each topic; that is, the parts of distribution $\bold{\phi}_k$, for $k \in {1,2}$, with the largest mass.

V <- dim(dtm)[2]

odd_rows <- rep(c(1,0), times = V)

Topic1 <- vb_fit$summary("phi")[odd_rows == 1,]

Topic2 <- vb_fit$summary("phi")[odd_rows == 0,]

word_probs <-data.frame(Topic = c(rep("Topic 1", V), rep("Topic 2", V)),

Word = rep(dtm$dimnames$Terms,N_TOPICS),

Probability = c(Topic1$mean, Topic2$mean))

# Selecting top 10 words per topic

top_words <- word_probs %>% group_by(Topic) %>%

top_n(10) %>% ungroup() %>% arrange(Topic, -Probability)

top_words %>%

mutate(Word = reorder_within(Word, Probability, Topic)) %>%

ggplot(aes(Probability, Word, fill = factor(Topic))) +

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

facet_wrap(~ Topic, scales = "free") +

scale_y_reordered() + theme(text = element_text(size = 15)) + xlim(0,0.025) +

xlab("Word distributions ( \u03d5 )")

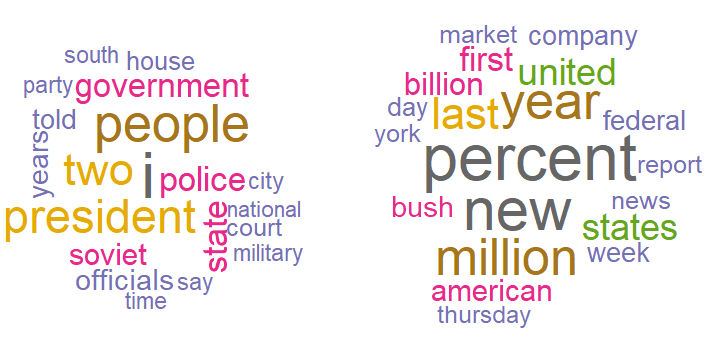

The most common words in topic 1 include people, government, president, police, and state, suggesting that this topic may represent political news. In contrast, the most common words in topic 2 include percent, billion, million, market, American, and states, hinting that this topic may represent news about the US economy. As the final note to document clustering with LDA, I will leave you with the code that creates word clouds with the most common words per topic using the wordcloud package.

top_words <- word_probs %>% group_by(Topic) %>% top_n(20) %>%

ungroup() %>% arrange(Topic, -Probability)

mycolors <- brewer.pal(8, "Dark2")

wordcloud(top_words %>% filter(Topic == "Topic 1") %>% .$Word ,

top_words %>% filter(Topic == "Topic 1") %>% .$Probability,

random.order = FALSE,

color = mycolors)

mycolors <- brewer.pal(8, "Dark2")

wordcloud(top_words %>% filter(Topic == "Topic 2") %>% .$Word ,

top_words %>% filter(Topic == "Topic 2") %>% .$Probability,

random.order = FALSE,

color = mycolors)

This text is an abbreviated version of Introducing Variational Inference in Statistics and Data Science Curriculum also published in The American Statistician.